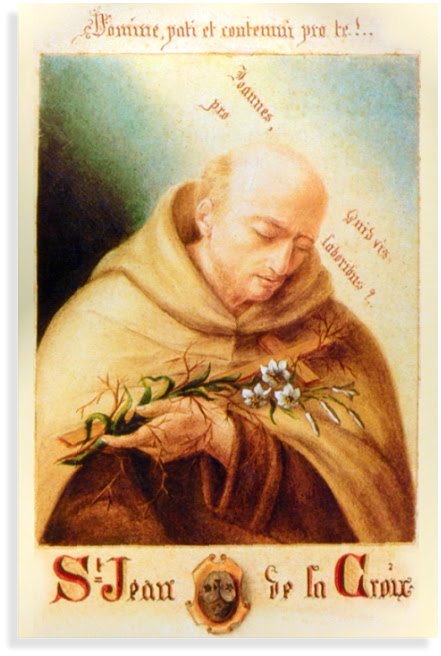

(St. John of the Cross painted by St. Therese's sister, Mother Agnes (Pauline)

Prayer to St. John of the Cross For His Intercession

O

glorious St. John of the Cross, through a pure desire of being like

Jesus crucified, you longed for nothing so eagerly as to suffer, to be

despised, and to be made little of by all; and your thirst after

sufferings was so burning that your noble heart rejoiced in the midst of

the cruelest torments and afflictions. Grant, I beseech you, O dear

Saint, by the glory which your many sufferings have gained for you, to

intercede for me and obtain from God for me a love of suffering,

together with strength and grace to bear with firmness of mind all the

trials and adversities which are the sure means

to the happy attainment of all that awaits me in heaven. Dear Saint,

from your most happy place in glory, hear, I beseech you, my prayers, so

that after your example, full of love for the cross I may deserve to be

your companion in glory. Amen.

Favorite Quotes from St. John of the Cross

- If you do not learn to deny yourself, you can make no progress in perfection.

- Where there is no love, pour love in and you will draw love out.

- In detachment, the spirit finds quiet and repose for coveting nothing.

- To be taken with love for a soul, God does not look on its greatness, but the greatness of its humility.

- The Lord measures our perfection neither by the multitude nor the magnitude of our deeds, but by the manner in which we perform them.

- I wish I could persuade spiritual persons that the way of perfection does not consist in many devices, nor in much cogitation, but in denying themselves completely and yielding themselves to suffer everything for the love of Christ.

- Live in the world as if only God and your soul were in it; then your heart will never be made captive by any earthly thing.

- O you souls who wish to go on with so much safety and consolation, if you knew how pleasing to God is suffering, and how much it helps in acquiring other good things, you would never seek consolation in anything; but you would rather look upon it as a great happiness to bear the Cross of the Lord.

- In giving us His Son, His only Word, He spoke everything to us at once in this sole Word -- and He has no more to say ... because what he spoke before to the prophets in parts, he has now spoken all at once by giving us the All Who is His Son.

- God desires the smallest degree of purity of conscience in you more than all the works you can perform.

- With what procrastinations do you wait, since from this very moment you can love God in your heart?

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yvKzLCYrEfE&feature]

When the family finally found work, John still went hungry in the middle of the wealthiest city in Spain. At fourteen, John took a job caring for hospital patients who suffered from incurable diseases and madness. It was out of this poverty and suffering, that John learned to search for beauty and happiness not in the world, but in God.

After John joined the Carmelite order, Saint Teresa of Avila asked him to help her reform movement. John supported her belief that the order should return to its life of prayer. But many Carmelites felt threatened by this reform, and some members of John's own order kidnapped him. He was locked in a cell six feet by ten feet and beaten three times a week by the monks. There was only one tiny window high up near the ceiling. Yet in that unbearable dark, cold, and desolation, his love and faith were like fire and light. He had nothing left but God -- and God brought John his greatest joys in that tiny cell.

After nine months, John escaped by unscrewing the lock on his door and creeping past the guard. Taking only the mystical poetry he had written in his cell, he climbed out a window using a rope made of stirps of blankets. With no idea where he was, he followed a dog to civilization. He hid from pursuers in a convent infirmary where he read his poetry to the nuns. From then on his life was devoted to sharing and explaining his experience of God's love.

His life of poverty and persecution could have produced a bitter cynic. Instead it gave birth to a compassionate mystic, who lived by the beliefs that "Who has ever seen people persuaded to love God by harshness?" and "Where there is no love, put love -- and you will find love."

John left us many books of practical advice on spiritual growth and prayer that are just as relevant today as they were then. These books include:

Ascent of Mount Carmel

Dark Night of the Soul

and A Spiritual Canticle of the Soul and the Bridegroom Christ

Since joy comes only from God, John believed that someone who seeks happiness in the world is like "a famished person who opens his mouth to satisfy himself with air." He taught that only by breaking the rope of our desires could we fly up to God. Above all, he was concerned for those who suffered dryness or depression in their spiritual life and offered encouragement that God loved them and was leading them deeper into faith.

"What more do you want, o soul! And what else do you search for outside, when within yourself you possess your riches, delights, satisfaction and kingdom -- your beloved whom you desire and seek? Desire him there, adore him there. Do not go in pursuit of him outside yourself. You will only become distracted and you won't find him, or enjoy him more than by seeking him within you." -- Saint John of the Cross

***This page, http://www.pathsoflove.com/john/LivingFlameLove.htm, has St. John of the Cross' full "The Living Flame of Love" online to read.

(St. John of the Cross with St. Teresa of Avila)

Early life and education

He was born Juan de Yepes y Álvarez[2] into a Jewish converso family in Fontiveros, near Ávila, a town of around 2,000 people.[3][4] His father, Gonzalo, was an accountant to richer relatives who were silk merchants. However, when in 1529 he married John's mother, Catalina, who was an orphan of a lower class, Gonzalo was rejected by his family and forced to work with his wife as a weaver.[5] John's father died in 1545, while John was still only around seven years old.[6] Two years later, John's older brother Luis died, probably as a result of insufficient nourishment caused by the penury to which John's family had been reduced. After this, John's mother Catalina took John and his surviving brother Francisco, and moved first in 1548 to Arevalo, and then in 1551 to Medina del Campo, where she was able to find work weaving.[7][8]In Medina, John entered a school for around 160[9] poor children, usually orphans, receiving a basic education, mainly in Christian doctrine, as well as some food, clothing, and lodging. While studying there, he was chosen to serve as acolyte at a nearby monastery of Augustinian nuns.[7] Growing up, John worked at a hospital and studied the humanities at a Jesuit school from 1559 to 1563; the Society of Jesus was a new organization at the time, having been founded only a few years earlier by the Spaniard St. Ignatius Loyola. In 1563[10] he entered the Carmelite Order, adopting the name John of St. Matthias.[7]

The following year (1564)[11] he professed his religious vows as a Carmelite and travelled to Salamanca, where he studied theology and philosophy at the prestigious University there (at the time one of the four biggest in Europe, alongside Paris, Oxford and Bologna) and at the Colegio de San Andrés. Some modern writers[citation needed] claim that this stay would influence all his later writings, as Fray Luis de León taught biblical studies (Exegesis, Hebrew and Aramaic) at the University: León was one of the foremost experts in Biblical Studies then and had written an important and controversial translation of the Song of Songs into Spanish. (Translation of the Bible into the vernacular was not allowed then in Spain.)

Joining the Reform of Teresa of Jesus

Statues representing John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila, in Beas de Segura

John

was ordained a priest in 1567, and then indicated his intent to join

the strict Carthusian Order, which appealed to him because of its

encouragement of solitary and silent contemplation. A journey from

Salamanca to Medina del Campo, probably in September 1567, changed this.[12]

In Medina he met the charismatic Carmelite nun, Teresa of Jesus. She

was in Medina to found the second of her convents for women.[13]

She immediately talked to him about her reformation projects for the

Order: she was seeking to restore the purity of the Carmelite Order by

restarting observance of its "Primitive Rule" of 1209, observance of

which had been relaxed by Pope Eugene IV in 1432.Under this Rule, much of the day and night was to be spent in the recitation of the choir offices, study and devotional reading, the celebration of Mass and times of solitude. For the friars, time was to be spent evangelizing the population around the monastery.[14] Total abstinence from meat and lengthy fasting was to be observed from the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross (September 14) until Easter. There were to be long periods of silence, especially between Compline and Prime. Coarser, shorter habits, more simple than those worn since 1432, were to be worn.[15] They were to follow the injunction against the wearing of shoes (also mitigated in 1432). It was from this last observance that the followers of Teresa among the Carmelites were becoming known as "discalced", i.e., barefoot, differentiating themselves from the non-reformed friars and nuns.

Teresa asked John to delay his entry into the Carthusians and to follow her.

Having spent a final year studying in Salamanca, in August 1568 John traveled with Teresa from Medina to Valladolid, where Teresa intended to found another monastery of nuns. Having spent some time with Teresa in Valladolid, learning more about this new form of Carmelite life, in October 1568, accompanied by Friar Antonio de Jesús de Heredia, John left Valladolid to found a new monastery for friars, the first for men following Teresa's principles. The were given the use of a derelict house at Duruelo (midway between Avila and Salamanca), which had been donated to Teresa. On 28 November 1568, the monastery,[16] was established, and on that same day John changed his name to John of the Cross.

Soon after, in June 1570, the friars found the house at Duruelo too small, and so moved to the nearby town of Mancera de Abajo. After moving on from this community, John set up a new community at Pastrana (October 1570), and a community at Alcalá de Henares, which was to be a house of studies for the academic training of the friars. In 1572[17] he arrived in Avila, at the invitation of Teresa, who had been appointed prioress of the Monastery of the Visitation there in 1571.[18] John become the spiritual director and confessor for Teresa and the other 130 nuns there, as well for as a wide range of laypeople in the city.[7] In 1574, John accompanied Teresa in the foundation of a new monastery in Segovia, returning to Avila after staying there a week. Beyond this, though, John seems to have remained in Avila between 1572 and 1577.[19]

Drawing of the crucifixion, by John of the Cross, which inspired Salvador Dali

The height of Carmelite tensions

The years 1575-77, however, saw a great increase in the tensions among the Spanish Carmelite friars over the reforms of Teresa and John. Since 1566 the reforms had been overseen by Canonical Visitors from the Dominican Order, with one appointed to Castile and a second to Andalusia. These Visitors had substantial powers: they could move the members of religious communities from house to house and even province to province. They could assist religious superiors in their office, and could depute other superiors from either the Dominicans or Carmelites. In Castile, the Visitor was Pedro Fernández, who prudently balanced the interests of the Discalced Carmelites against those of the friars and nuns who did not desire reform.[20]In Andalusia to the south, however, where the Visitor was Francisco Vargas, tensions rose due to his clear preference for the Discalced friars. Vargas asked them to make foundations in various cities, in explicit contradiction of orders from the Carmelite Prior General against their expansion in Andalusia. As a result, a General Chapter of the Carmelite Order was convened at Piacenza in Italy in May 1575, out of concern that events in Spain were getting out of hand, which concluded by ordering the total suppression of the Discalced houses.[7]

This measure was not immediately enforced. For one thing, King Philip II of Spain was supportive of some of Teresa’s reforms, and so was not immediately willing to grant the necessary permission to enforce this ordinance. Moreover the Discalced friars also found support from the papal nuncio to King Philip II, Nicolò Ormanetto, Bishop of Padua, who still had ultimate power as nuncio to visit and reform religious Orders. When asked by the Discalced friars to intervene, Ormanetto replaced Vargas as Visitor of the Carmelites in Andalusia (where the troubles had begun) with Jerónimo Gracián, a priest from the University of Alcalá, who was in fact a Discalced Carmelite friar himself.[7] The nuncio's protection helped John himself avoid problems for a time. In January 1576 John was arrested in Medina del Campo by some Carmelite friars.

However, through the nuncio's intervention, John was soon released.[7] When Ormanetto died on 18 June 1577, however, John was left without protection, and the friars opposing his reforms gained the upper hand.

Imprisonment, writings, torture, death and recognition

On the night of 2 December 1577, a group of Carmelites opposed to reform broke into John’s dwelling in Avila, and took him prisoner.

El

Greco's landscape of Toledo depicts the Priory in which John was held

captive, just below the old Muslim Alcazar and perched on the banks of

the Tajo on high cliffsJohn had received an order

from some of his superiors, opposed to reform, ordering him to leave

Avila and return to his original house, but John had refused on the

basis that his reform work had been approved by the Spanish Nuncio, a

higher authority than these superiors.[21]

The Carmelites therefore took John captive. John was taken from Avila

to the Carmelite monastery in Toledo, at that time the Order's most

important monastery in Castile, where perhaps 40 friars lived.[22][23]

John was brought before a court of friars, accused of disobeying the

ordinances of Piacenza. Despite John's argument that he had not

disobeyed the ordinances, he received a punishment of imprisonment. He

was jailed in the monastery, where he was kept under a brutal regimen

that included public lashing before the community at least weekly, and

severe isolation in a tiny stifling cell measuring ten feet by six feet,

barely large enough for his body. Except when rarely permitted an oil

lamp, he had to stand on a bench to read his breviary by the light

through the hole into the adjoining room. He had no change of clothing

and a penitential diet of water, bread and scraps of salt fish.[24] During this imprisonment, he composed a great part of his most famous poem Spiritual Canticle, as well as a few shorter poems. The paper was passed to him by the friar who guarded his cell.[25]

He managed to escape nine months later, on 15 August 1578, through a

small window in a room adjoining his cell. (He had managed to pry the

cell door off its hinges earlier that day).

At this meeting John was appointed superior of El Calvario, an isolated monastery of around thirty friars in the mountains about 6 miles away[27] from Beas in Andalucia. During this time he befriended the nun Ana de Jesús, superior of the Discalced nuns at Beas, through his visits every Saturday to the town. While at El Calvario he composed his first version of his commentary on his poem, The Spiritual Canticle, perhaps at the request of the nuns in Beas.

In 1579 he moved to Baeza, a town of around 50,000 people, to serve as rector of a new college, the Colegio de San Basilio, to support the studies of Discalced friars in Andalucia. This opened on 13 June 1579, and he remained there until 1582, spending much of his time as a spiritual director for the friars and townspeople.

1580 was an important year in the resolution of the disputes within the Carmelites. On 22 June, Pope Gregory XIII signed a decree, titled Pia Consideratione, which authorised a separation between the Calced and Discalced Carmelites. The Dominican friar, Juan Velázquez de las Cuevas, was appointed to carry out the decisions. At the first General Chapter of the Discalced Carmelites, in Alcalá de Henares on 3 March 1581, John of the Cross was elected one of the ‘Definitors’ of the community, and wrote a set of constitutions for them.[28] By the time of the Provincial Chapter at Alcalá in 1581, there were 22 houses, some 300 friars and 200 nuns in the Discalced Carmelites.[29]

Saint John of the Cross' shrine and reliquary, Convent of Carmelite Friars, Segovia

Reliquary of John of the Cross in Úbeda, Spain

In February 1585, John travelled to Malaga and established a monastery of Discalced nuns there. In May 1585, at the General Chapter of the Discalced Carmelites in Lisbon, John was elected Provincial Vicar of Andalusia, a post which required him to travel frequently, making annual visitations of the houses of friars and nuns in Andalusia. During this time he founded seven new monasteries in the region, and is estimated to have travelled around 25,000 km.[31]

In June 1588, he was elected third Councillor to the Vicar General for the Discalced Carmelites, Father Nicolas Doria. To fulfill this role, he had to return to Segovia in Castile, where in this capacity he was also prior of the monastery. After disagreeing in 1590-1 with some of Doria's remodeling of the leadership of the Discalced Carmelite Order, though, John was removed from his post in Segovia, and sent by Doria in June 1591 to an isolated monastery in Andalusia called La Peñuela. There he fell ill, and traveled to the monastery at Úbeda for treatment. His condition worsened, however, and he died there on 14 December 1591, of erysipelas.[7]

Veneration

The morning after John’s death, huge numbers of the townspeople of Úbeda entered the monastery to view John’s body; in the crush, many were able to take home parts of his habit. He was initially buried at Úbeda, but, at the request of the monastery in Segovia, his body was secretly moved there in 1593. The people of Úbeda, however, unhappy at this change, sent representative to petition the pope to move the body back to its original resting place. Pope Clement VIII, impressed by the petition, issued a Brief on 15 October 1596 ordering the return of the body to Ubeda. Eventually, in a compromise, the superiors of the Discalced Carmelites decided that the monastery at Úbeda would receive one leg and one arm of the corpse from Segovia (the monastery at Úbeda had already kept one leg in 1593, and the other arm had been removed as the corpse passed through Madrid in 1593, to form a relic there). A hand and a leg remain visible in a reliquary at the Oratory of San Juan de la Cruz in Úbeda, a monastery built in 1627 though connected to the original Discalced monastery in the town founded in 1587.[32]The head and torso was retained by the monastery at Segovia. There, they were venerated until 1647, when on orders from Rome designed to prevent the veneration of remains without official approval, the remains were buried in the ground. In the 1930s they were disinterred, and now sit in a side chapel in a marble case above a special altar built in that decade.[32]

Proceedings to beatify John began with the gathering of information on his life between 1614 and 1616, although he was only beatified in 1675 by Pope Clement X, and was canonized by Benedict XIII in 1726. When his feast day was added to the General Roman Calendar in 1738, it was assigned to 24 November, since his date of death was impeded by the then-existing octave of the Feast of the Immaculate Conception.[33] This obstacle was removed in 1955 and in 1969 Pope Paul VI moved it to the dies natalis (birthday to heaven) of the saint, 14 December.[34] The Church of England commemorates him as a "Teacher of the Faith" on the same date. In 1926, he was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XI.

Editions of his works

His writings were first published in 1618 by Diego de Salablanca. The numerical divisions in the work, still used by modern editions of the text, were introduced by Salablanca (they were not in John's original writings), in order to help make the work more manageable for the reader.[7] This edition does not contain the ‘’Spiritual Canticle’’, however, and also omits or adapts certain passages, perhaps for fear of falling foul of the Inquisition.The ‘’Spiritual Canticle’’ was first included in the 1630 edition, produced by Fray Jeronimo de San Jose, at Madrid. This edition was largely followed by later editors, although editions in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries gradually included a few more poems and letters.[35]

Literary works

St. John of the Cross is considered one of the foremost poets in the Spanish language. Although his complete poems add up to fewer than 2500 verses, two of them—the Spiritual Canticle and The Dark Night of the Soul are widely considered masterpieces of Spanish poetry, both for their formal stylistic point of view and their rich symbolism and imagery. His theological works often consist of commentaries on these poems. All the works were written between 1578 and his death in 1591, meaning there is great consistency in the views presented in them.The poem The Spiritual Canticle, is an eclogue in which the bride (representing the soul) searches for the bridegroom (representing Jesus Christ), and is anxious at having lost him; both are filled with joy upon reuniting. It can be seen as a free-form Spanish version of the Song of Songs at a time when translations of the Bible into the vernacular were forbidden. The first 31 stanzas of the poem were composed in 1578 while John was imprisoned in Toledo. It was read after his escape by the nuns at Beas, who made copies of these stanzas. Over the following years, John added some extra stanzas. Today, two versions exist: one with 39 stanzas and one with 40, although with some of the stanzas ordered differently. The first redaction of the commentary on the poem was written in 1584, at the request of Madre Ana de Jesus, when she was prioress of the Discalced Carmelite nuns in Granada. A second redaction, which contains more detail, was written in 1585-6.[7]

The Dark Night (from which the spiritual term takes its name) narrates the journey of the soul from her bodily home to her union with God. It happens during the night, which represents the hardships and difficulties she meets in detachment from the world and reaching the light of the union with the Creator. There are several steps in this night, which are related in successive stanzas. The main idea of the poem can be seen as the painful experience that people endure as they seek to grow in spiritual maturity and union with God. The poem of this title was likely written in 1578 or 1579. In 1584-5, John wrote a commentary on the first two stanzas and first line of the third stanza of the poem.[7]

The Ascent of Mount Carmel is a more systematic study of the ascetical endeavour of a soul looking for perfect union, God, and the mystical events happening along the way. Although it begins as a commentary on the poem ‘’The Dark Night’’, it rapidly drops this format, having commented on the first two stanzas of the poem, and becomes a treatise. It was composed sometime between 1581 and 1585.[7]

A four stanza work, Living Flame of Love describes a greater intimacy, as the soul responds to God's love. It was written in a first redaction at Granada between 1585-6, apparently in two wToday is the Solemnity of St. John of the Cross seeks,[7] and in a mostly identical second redaction at La Penuela in 1591.

These, together with his Dichos de Luz y Amor, or "Sayings of Light and Love," and St. Teresa's writings, are the most important mystical works in Spanish, and have deeply influenced later spiritual writers all around the world. Among these can be named T. S. Eliot, Thérèse de Lisieux, Edith Stein (Teresa Benedicta of the Cross), and Thomas Merton. John has also influenced philosophers (Jacques Maritain), theologians (Hans Urs von Balthasar), pacifists (Dorothy Day, Daniel Berrigan, and Philip Berrigan) and artists (Salvador Dalí). Pope John Paul II wrote his theological dissertation on the mystical theology of Saint John of the Cross.

No comments:

Post a Comment