Search This Blog

Thursday, December 13, 2012

Read St. John of the Cross' Works Online

(St. John of the Cross imprisoned.)

A great site with the works of St. John of the Cross online:

http://www.jesus-passion.com/John_of_the_Cross.htm

LITANY OF ST. JOHN OF THE CROSS - for his Solemnity

LITANY OF ST. JOHN OF THE CROSS

Lord, have mercy on us.

Christ, have mercy on us.

Lord, have mercy on us. Christ hear us.

Christ, graciously hear us.

God the Father of Heaven, Have mercy on us.

God the Son, Redeemer of the world, Have mercy on us.

God the Holy Ghost, Have mercy on us.

Holy Trinity, one God, Have mercy on us.

Holy Mary, Mother of God, Pray for us.

Queen and Beauty of Carmel, Pray for us.

Saint John of the Cross, Pray for us.

St. John, our glorious Father, Pray for us.

Beloved child of Mary, the Queen of Carmel, Pray for us.

Fragrant flower of the garden of Carmel, Pray for us.

Admirable possessor of the spirit of Elias, Pray for us.

Foundation stone of the Carmelite Reform, Pray for us.

Spiritual son, and beloved Father of St. Teresa, Pray for us.

Most vigilant in the practice of virtue, Pray for us.

Treasure of charity, Pray for us.

Abyss of humility, Pray for us.

Most perfect in obedience, Pray for us.

Invincible in patience, Pray for us.

Constant lover of poverty, Pray for us.

Dove of simplicity, Pray for us.

Thirsting for mortification, Pray for us.

Prodigy of holiness, Pray for us.

Mystical Doctor, Pray for us.

Model of contemplation, Pray for us.

Zealous preacher of the Word of God, Pray for us.

Worker of miracles, Pray for us.

Bringing joy and peace to souls, Pray for us.

Terror of devils, Pray for us.

Model of penance, Pray for us.

Faithful guardian of Christ's Vineyard, Pray for us.

Ornament and glory of Carmel, Pray for us.

Lamb of God, Who takest away the sins of the world: Spare us, O Lord.

Lamb of God, Who takest away the sins of the world: Graciously hear us, O Lord.

Lamb of God, Who takest away the sins of the world: Have mercy on us.

V. Holy Father Saint John of the Cross, pray for us:

R. That we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ.

Let us pray.

O God, Who didst instill into the heart of Saint John of the Cross, Thy Confessor and our Father, a perfect spirit of self-abnegation, and a surpassing love of Thy Cross: grant, that assiduously following in his footsteps, we may attain to eternal glory. Through Christ Our Lord. R. Amen.

Today is the Solemnity of St. John of the Cross

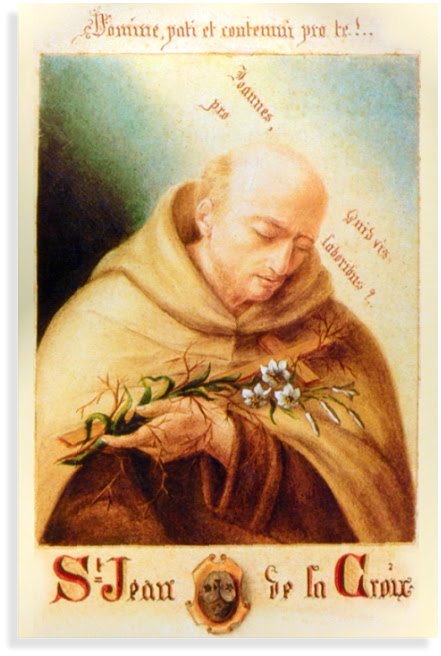

(St. John of the Cross painted by St. Therese's sister, Mother Agnes (Pauline)

Prayer to St. John of the Cross For His Intercession

O

glorious St. John of the Cross, through a pure desire of being like

Jesus crucified, you longed for nothing so eagerly as to suffer, to be

despised, and to be made little of by all; and your thirst after

sufferings was so burning that your noble heart rejoiced in the midst of

the cruelest torments and afflictions. Grant, I beseech you, O dear

Saint, by the glory which your many sufferings have gained for you, to

intercede for me and obtain from God for me a love of suffering,

together with strength and grace to bear with firmness of mind all the

trials and adversities which are the sure means

to the happy attainment of all that awaits me in heaven. Dear Saint,

from your most happy place in glory, hear, I beseech you, my prayers, so

that after your example, full of love for the cross I may deserve to be

your companion in glory. Amen.

Favorite Quotes from St. John of the Cross

- If you do not learn to deny yourself, you can make no progress in perfection.

- Where there is no love, pour love in and you will draw love out.

- In detachment, the spirit finds quiet and repose for coveting nothing.

- To be taken with love for a soul, God does not look on its greatness, but the greatness of its humility.

- The Lord measures our perfection neither by the multitude nor the magnitude of our deeds, but by the manner in which we perform them.

- I wish I could persuade spiritual persons that the way of perfection does not consist in many devices, nor in much cogitation, but in denying themselves completely and yielding themselves to suffer everything for the love of Christ.

- Live in the world as if only God and your soul were in it; then your heart will never be made captive by any earthly thing.

- O you souls who wish to go on with so much safety and consolation, if you knew how pleasing to God is suffering, and how much it helps in acquiring other good things, you would never seek consolation in anything; but you would rather look upon it as a great happiness to bear the Cross of the Lord.

- In giving us His Son, His only Word, He spoke everything to us at once in this sole Word -- and He has no more to say ... because what he spoke before to the prophets in parts, he has now spoken all at once by giving us the All Who is His Son.

- God desires the smallest degree of purity of conscience in you more than all the works you can perform.

- With what procrastinations do you wait, since from this very moment you can love God in your heart?

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yvKzLCYrEfE&feature]

When the family finally found work, John still went hungry in the middle of the wealthiest city in Spain. At fourteen, John took a job caring for hospital patients who suffered from incurable diseases and madness. It was out of this poverty and suffering, that John learned to search for beauty and happiness not in the world, but in God.

After John joined the Carmelite order, Saint Teresa of Avila asked him to help her reform movement. John supported her belief that the order should return to its life of prayer. But many Carmelites felt threatened by this reform, and some members of John's own order kidnapped him. He was locked in a cell six feet by ten feet and beaten three times a week by the monks. There was only one tiny window high up near the ceiling. Yet in that unbearable dark, cold, and desolation, his love and faith were like fire and light. He had nothing left but God -- and God brought John his greatest joys in that tiny cell.

After nine months, John escaped by unscrewing the lock on his door and creeping past the guard. Taking only the mystical poetry he had written in his cell, he climbed out a window using a rope made of stirps of blankets. With no idea where he was, he followed a dog to civilization. He hid from pursuers in a convent infirmary where he read his poetry to the nuns. From then on his life was devoted to sharing and explaining his experience of God's love.

His life of poverty and persecution could have produced a bitter cynic. Instead it gave birth to a compassionate mystic, who lived by the beliefs that "Who has ever seen people persuaded to love God by harshness?" and "Where there is no love, put love -- and you will find love."

John left us many books of practical advice on spiritual growth and prayer that are just as relevant today as they were then. These books include:

Ascent of Mount Carmel

Dark Night of the Soul

and A Spiritual Canticle of the Soul and the Bridegroom Christ

Since joy comes only from God, John believed that someone who seeks happiness in the world is like "a famished person who opens his mouth to satisfy himself with air." He taught that only by breaking the rope of our desires could we fly up to God. Above all, he was concerned for those who suffered dryness or depression in their spiritual life and offered encouragement that God loved them and was leading them deeper into faith.

"What more do you want, o soul! And what else do you search for outside, when within yourself you possess your riches, delights, satisfaction and kingdom -- your beloved whom you desire and seek? Desire him there, adore him there. Do not go in pursuit of him outside yourself. You will only become distracted and you won't find him, or enjoy him more than by seeking him within you." -- Saint John of the Cross

***This page, http://www.pathsoflove.com/john/LivingFlameLove.htm, has St. John of the Cross' full "The Living Flame of Love" online to read.

(St. John of the Cross with St. Teresa of Avila)

Early life and education

He was born Juan de Yepes y Álvarez[2] into a Jewish converso family in Fontiveros, near Ávila, a town of around 2,000 people.[3][4] His father, Gonzalo, was an accountant to richer relatives who were silk merchants. However, when in 1529 he married John's mother, Catalina, who was an orphan of a lower class, Gonzalo was rejected by his family and forced to work with his wife as a weaver.[5] John's father died in 1545, while John was still only around seven years old.[6] Two years later, John's older brother Luis died, probably as a result of insufficient nourishment caused by the penury to which John's family had been reduced. After this, John's mother Catalina took John and his surviving brother Francisco, and moved first in 1548 to Arevalo, and then in 1551 to Medina del Campo, where she was able to find work weaving.[7][8]In Medina, John entered a school for around 160[9] poor children, usually orphans, receiving a basic education, mainly in Christian doctrine, as well as some food, clothing, and lodging. While studying there, he was chosen to serve as acolyte at a nearby monastery of Augustinian nuns.[7] Growing up, John worked at a hospital and studied the humanities at a Jesuit school from 1559 to 1563; the Society of Jesus was a new organization at the time, having been founded only a few years earlier by the Spaniard St. Ignatius Loyola. In 1563[10] he entered the Carmelite Order, adopting the name John of St. Matthias.[7]

The following year (1564)[11] he professed his religious vows as a Carmelite and travelled to Salamanca, where he studied theology and philosophy at the prestigious University there (at the time one of the four biggest in Europe, alongside Paris, Oxford and Bologna) and at the Colegio de San Andrés. Some modern writers[citation needed] claim that this stay would influence all his later writings, as Fray Luis de León taught biblical studies (Exegesis, Hebrew and Aramaic) at the University: León was one of the foremost experts in Biblical Studies then and had written an important and controversial translation of the Song of Songs into Spanish. (Translation of the Bible into the vernacular was not allowed then in Spain.)

Joining the Reform of Teresa of Jesus

Statues representing John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila, in Beas de Segura

John

was ordained a priest in 1567, and then indicated his intent to join

the strict Carthusian Order, which appealed to him because of its

encouragement of solitary and silent contemplation. A journey from

Salamanca to Medina del Campo, probably in September 1567, changed this.[12]

In Medina he met the charismatic Carmelite nun, Teresa of Jesus. She

was in Medina to found the second of her convents for women.[13]

She immediately talked to him about her reformation projects for the

Order: she was seeking to restore the purity of the Carmelite Order by

restarting observance of its "Primitive Rule" of 1209, observance of

which had been relaxed by Pope Eugene IV in 1432.Under this Rule, much of the day and night was to be spent in the recitation of the choir offices, study and devotional reading, the celebration of Mass and times of solitude. For the friars, time was to be spent evangelizing the population around the monastery.[14] Total abstinence from meat and lengthy fasting was to be observed from the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross (September 14) until Easter. There were to be long periods of silence, especially between Compline and Prime. Coarser, shorter habits, more simple than those worn since 1432, were to be worn.[15] They were to follow the injunction against the wearing of shoes (also mitigated in 1432). It was from this last observance that the followers of Teresa among the Carmelites were becoming known as "discalced", i.e., barefoot, differentiating themselves from the non-reformed friars and nuns.

Teresa asked John to delay his entry into the Carthusians and to follow her.

Having spent a final year studying in Salamanca, in August 1568 John traveled with Teresa from Medina to Valladolid, where Teresa intended to found another monastery of nuns. Having spent some time with Teresa in Valladolid, learning more about this new form of Carmelite life, in October 1568, accompanied by Friar Antonio de Jesús de Heredia, John left Valladolid to found a new monastery for friars, the first for men following Teresa's principles. The were given the use of a derelict house at Duruelo (midway between Avila and Salamanca), which had been donated to Teresa. On 28 November 1568, the monastery,[16] was established, and on that same day John changed his name to John of the Cross.

Soon after, in June 1570, the friars found the house at Duruelo too small, and so moved to the nearby town of Mancera de Abajo. After moving on from this community, John set up a new community at Pastrana (October 1570), and a community at Alcalá de Henares, which was to be a house of studies for the academic training of the friars. In 1572[17] he arrived in Avila, at the invitation of Teresa, who had been appointed prioress of the Monastery of the Visitation there in 1571.[18] John become the spiritual director and confessor for Teresa and the other 130 nuns there, as well for as a wide range of laypeople in the city.[7] In 1574, John accompanied Teresa in the foundation of a new monastery in Segovia, returning to Avila after staying there a week. Beyond this, though, John seems to have remained in Avila between 1572 and 1577.[19]

Drawing of the crucifixion, by John of the Cross, which inspired Salvador Dali

The height of Carmelite tensions

The years 1575-77, however, saw a great increase in the tensions among the Spanish Carmelite friars over the reforms of Teresa and John. Since 1566 the reforms had been overseen by Canonical Visitors from the Dominican Order, with one appointed to Castile and a second to Andalusia. These Visitors had substantial powers: they could move the members of religious communities from house to house and even province to province. They could assist religious superiors in their office, and could depute other superiors from either the Dominicans or Carmelites. In Castile, the Visitor was Pedro Fernández, who prudently balanced the interests of the Discalced Carmelites against those of the friars and nuns who did not desire reform.[20]In Andalusia to the south, however, where the Visitor was Francisco Vargas, tensions rose due to his clear preference for the Discalced friars. Vargas asked them to make foundations in various cities, in explicit contradiction of orders from the Carmelite Prior General against their expansion in Andalusia. As a result, a General Chapter of the Carmelite Order was convened at Piacenza in Italy in May 1575, out of concern that events in Spain were getting out of hand, which concluded by ordering the total suppression of the Discalced houses.[7]

This measure was not immediately enforced. For one thing, King Philip II of Spain was supportive of some of Teresa’s reforms, and so was not immediately willing to grant the necessary permission to enforce this ordinance. Moreover the Discalced friars also found support from the papal nuncio to King Philip II, Nicolò Ormanetto, Bishop of Padua, who still had ultimate power as nuncio to visit and reform religious Orders. When asked by the Discalced friars to intervene, Ormanetto replaced Vargas as Visitor of the Carmelites in Andalusia (where the troubles had begun) with Jerónimo Gracián, a priest from the University of Alcalá, who was in fact a Discalced Carmelite friar himself.[7] The nuncio's protection helped John himself avoid problems for a time. In January 1576 John was arrested in Medina del Campo by some Carmelite friars.

However, through the nuncio's intervention, John was soon released.[7] When Ormanetto died on 18 June 1577, however, John was left without protection, and the friars opposing his reforms gained the upper hand.

Imprisonment, writings, torture, death and recognition

On the night of 2 December 1577, a group of Carmelites opposed to reform broke into John’s dwelling in Avila, and took him prisoner.

El

Greco's landscape of Toledo depicts the Priory in which John was held

captive, just below the old Muslim Alcazar and perched on the banks of

the Tajo on high cliffsJohn had received an order

from some of his superiors, opposed to reform, ordering him to leave

Avila and return to his original house, but John had refused on the

basis that his reform work had been approved by the Spanish Nuncio, a

higher authority than these superiors.[21]

The Carmelites therefore took John captive. John was taken from Avila

to the Carmelite monastery in Toledo, at that time the Order's most

important monastery in Castile, where perhaps 40 friars lived.[22][23]

John was brought before a court of friars, accused of disobeying the

ordinances of Piacenza. Despite John's argument that he had not

disobeyed the ordinances, he received a punishment of imprisonment. He

was jailed in the monastery, where he was kept under a brutal regimen

that included public lashing before the community at least weekly, and

severe isolation in a tiny stifling cell measuring ten feet by six feet,

barely large enough for his body. Except when rarely permitted an oil

lamp, he had to stand on a bench to read his breviary by the light

through the hole into the adjoining room. He had no change of clothing

and a penitential diet of water, bread and scraps of salt fish.[24] During this imprisonment, he composed a great part of his most famous poem Spiritual Canticle, as well as a few shorter poems. The paper was passed to him by the friar who guarded his cell.[25]

He managed to escape nine months later, on 15 August 1578, through a

small window in a room adjoining his cell. (He had managed to pry the

cell door off its hinges earlier that day).

At this meeting John was appointed superior of El Calvario, an isolated monastery of around thirty friars in the mountains about 6 miles away[27] from Beas in Andalucia. During this time he befriended the nun Ana de Jesús, superior of the Discalced nuns at Beas, through his visits every Saturday to the town. While at El Calvario he composed his first version of his commentary on his poem, The Spiritual Canticle, perhaps at the request of the nuns in Beas.

In 1579 he moved to Baeza, a town of around 50,000 people, to serve as rector of a new college, the Colegio de San Basilio, to support the studies of Discalced friars in Andalucia. This opened on 13 June 1579, and he remained there until 1582, spending much of his time as a spiritual director for the friars and townspeople.

1580 was an important year in the resolution of the disputes within the Carmelites. On 22 June, Pope Gregory XIII signed a decree, titled Pia Consideratione, which authorised a separation between the Calced and Discalced Carmelites. The Dominican friar, Juan Velázquez de las Cuevas, was appointed to carry out the decisions. At the first General Chapter of the Discalced Carmelites, in Alcalá de Henares on 3 March 1581, John of the Cross was elected one of the ‘Definitors’ of the community, and wrote a set of constitutions for them.[28] By the time of the Provincial Chapter at Alcalá in 1581, there were 22 houses, some 300 friars and 200 nuns in the Discalced Carmelites.[29]

Saint John of the Cross' shrine and reliquary, Convent of Carmelite Friars, Segovia

Reliquary of John of the Cross in Úbeda, Spain

In February 1585, John travelled to Malaga and established a monastery of Discalced nuns there. In May 1585, at the General Chapter of the Discalced Carmelites in Lisbon, John was elected Provincial Vicar of Andalusia, a post which required him to travel frequently, making annual visitations of the houses of friars and nuns in Andalusia. During this time he founded seven new monasteries in the region, and is estimated to have travelled around 25,000 km.[31]

In June 1588, he was elected third Councillor to the Vicar General for the Discalced Carmelites, Father Nicolas Doria. To fulfill this role, he had to return to Segovia in Castile, where in this capacity he was also prior of the monastery. After disagreeing in 1590-1 with some of Doria's remodeling of the leadership of the Discalced Carmelite Order, though, John was removed from his post in Segovia, and sent by Doria in June 1591 to an isolated monastery in Andalusia called La Peñuela. There he fell ill, and traveled to the monastery at Úbeda for treatment. His condition worsened, however, and he died there on 14 December 1591, of erysipelas.[7]

Veneration

The morning after John’s death, huge numbers of the townspeople of Úbeda entered the monastery to view John’s body; in the crush, many were able to take home parts of his habit. He was initially buried at Úbeda, but, at the request of the monastery in Segovia, his body was secretly moved there in 1593. The people of Úbeda, however, unhappy at this change, sent representative to petition the pope to move the body back to its original resting place. Pope Clement VIII, impressed by the petition, issued a Brief on 15 October 1596 ordering the return of the body to Ubeda. Eventually, in a compromise, the superiors of the Discalced Carmelites decided that the monastery at Úbeda would receive one leg and one arm of the corpse from Segovia (the monastery at Úbeda had already kept one leg in 1593, and the other arm had been removed as the corpse passed through Madrid in 1593, to form a relic there). A hand and a leg remain visible in a reliquary at the Oratory of San Juan de la Cruz in Úbeda, a monastery built in 1627 though connected to the original Discalced monastery in the town founded in 1587.[32]The head and torso was retained by the monastery at Segovia. There, they were venerated until 1647, when on orders from Rome designed to prevent the veneration of remains without official approval, the remains were buried in the ground. In the 1930s they were disinterred, and now sit in a side chapel in a marble case above a special altar built in that decade.[32]

Proceedings to beatify John began with the gathering of information on his life between 1614 and 1616, although he was only beatified in 1675 by Pope Clement X, and was canonized by Benedict XIII in 1726. When his feast day was added to the General Roman Calendar in 1738, it was assigned to 24 November, since his date of death was impeded by the then-existing octave of the Feast of the Immaculate Conception.[33] This obstacle was removed in 1955 and in 1969 Pope Paul VI moved it to the dies natalis (birthday to heaven) of the saint, 14 December.[34] The Church of England commemorates him as a "Teacher of the Faith" on the same date. In 1926, he was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XI.

Editions of his works

His writings were first published in 1618 by Diego de Salablanca. The numerical divisions in the work, still used by modern editions of the text, were introduced by Salablanca (they were not in John's original writings), in order to help make the work more manageable for the reader.[7] This edition does not contain the ‘’Spiritual Canticle’’, however, and also omits or adapts certain passages, perhaps for fear of falling foul of the Inquisition.The ‘’Spiritual Canticle’’ was first included in the 1630 edition, produced by Fray Jeronimo de San Jose, at Madrid. This edition was largely followed by later editors, although editions in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries gradually included a few more poems and letters.[35]

Literary works

St. John of the Cross is considered one of the foremost poets in the Spanish language. Although his complete poems add up to fewer than 2500 verses, two of them—the Spiritual Canticle and The Dark Night of the Soul are widely considered masterpieces of Spanish poetry, both for their formal stylistic point of view and their rich symbolism and imagery. His theological works often consist of commentaries on these poems. All the works were written between 1578 and his death in 1591, meaning there is great consistency in the views presented in them.The poem The Spiritual Canticle, is an eclogue in which the bride (representing the soul) searches for the bridegroom (representing Jesus Christ), and is anxious at having lost him; both are filled with joy upon reuniting. It can be seen as a free-form Spanish version of the Song of Songs at a time when translations of the Bible into the vernacular were forbidden. The first 31 stanzas of the poem were composed in 1578 while John was imprisoned in Toledo. It was read after his escape by the nuns at Beas, who made copies of these stanzas. Over the following years, John added some extra stanzas. Today, two versions exist: one with 39 stanzas and one with 40, although with some of the stanzas ordered differently. The first redaction of the commentary on the poem was written in 1584, at the request of Madre Ana de Jesus, when she was prioress of the Discalced Carmelite nuns in Granada. A second redaction, which contains more detail, was written in 1585-6.[7]

The Dark Night (from which the spiritual term takes its name) narrates the journey of the soul from her bodily home to her union with God. It happens during the night, which represents the hardships and difficulties she meets in detachment from the world and reaching the light of the union with the Creator. There are several steps in this night, which are related in successive stanzas. The main idea of the poem can be seen as the painful experience that people endure as they seek to grow in spiritual maturity and union with God. The poem of this title was likely written in 1578 or 1579. In 1584-5, John wrote a commentary on the first two stanzas and first line of the third stanza of the poem.[7]

The Ascent of Mount Carmel is a more systematic study of the ascetical endeavour of a soul looking for perfect union, God, and the mystical events happening along the way. Although it begins as a commentary on the poem ‘’The Dark Night’’, it rapidly drops this format, having commented on the first two stanzas of the poem, and becomes a treatise. It was composed sometime between 1581 and 1585.[7]

A four stanza work, Living Flame of Love describes a greater intimacy, as the soul responds to God's love. It was written in a first redaction at Granada between 1585-6, apparently in two wToday is the Solemnity of St. John of the Cross seeks,[7] and in a mostly identical second redaction at La Penuela in 1591.

These, together with his Dichos de Luz y Amor, or "Sayings of Light and Love," and St. Teresa's writings, are the most important mystical works in Spanish, and have deeply influenced later spiritual writers all around the world. Among these can be named T. S. Eliot, Thérèse de Lisieux, Edith Stein (Teresa Benedicta of the Cross), and Thomas Merton. John has also influenced philosophers (Jacques Maritain), theologians (Hans Urs von Balthasar), pacifists (Dorothy Day, Daniel Berrigan, and Philip Berrigan) and artists (Salvador Dalí). Pope John Paul II wrote his theological dissertation on the mystical theology of Saint John of the Cross.

Tuesday, December 4, 2012

May all have a blessed and fruitful Advent!

Advent - 3rd Day

"As the deer longs for the source

of living water.

So to you, Lord, I fly and I'm coming."

"As the deer longs for the source

of living water.

So to you, Lord, I fly and I'm coming."

Monday, December 3, 2012

"Say Merry Christmas" - Don't shop at stores that don't say "Merry Christmas" or try to erase Christ from Christmas!!

Download your FREE Sheet Music at www.saymerrychristmas.net and together we can make 'Say Merry Christmas' the biggest Christmas song of all time. Also available on iTunes and Amazon.

Besides not shopping there, do take time and tell the staff, manager, owner WHY you are NOT shopping there! Perhaps if it hurts their pockets, they will rethink their actions!

Saturday, December 1, 2012

ADVENT WITH THE VISITANDINE NUNS

The Visitation Order founded by St. Jane de Chantal and St. Francis de Sales is very close to Carmel. St. Therese when she lived at home, and perhaps in Carmel, read the writings of St. Francis de Sales. Her "Little Way" is almost identical to St. Francis' writings as he too taught a "little way". Also, St. Therese's blood sister, Leonie, entered the Visitation monastery in Caen, France and became Sr. Francois Therese (Therese after her sister, St. Therese). So it is not strange to put some of the Visitation order's saints and their writings on a blog all about Carmel!

From http://visitationspirit.org/blog/:

We begin with newly declared Venerable Sister Maria Margit Bogner, VHM of Erd, Hungary (1905-1933) whose Cause for beatification is in process. In

a private audience this past June 2012, with prefect of the

Congregation for the Causes of the Saints, Cardinal Angelo Amato, Pope

Benedict XVI approved the “heroic virtue” of Servant of God Maria

Margit Bogner.

We begin with newly declared Venerable Sister Maria Margit Bogner, VHM of Erd, Hungary (1905-1933) whose Cause for beatification is in process. In

a private audience this past June 2012, with prefect of the

Congregation for the Causes of the Saints, Cardinal Angelo Amato, Pope

Benedict XVI approved the “heroic virtue” of Servant of God Maria

Margit Bogner.

Sister Maria Margit lived the liturgical seasons fully, both interiorly and in community. Her interior reflections and prayers were manifested in her diaries and other journal writings. We take these excerpts from the book “Une Tombe Pres du Danube”by Elemer Csavossy SJ, in French, translated by the current blogger.

Sister Maria Margit’s ardor grew throughout Advent. She also prayed in conjunction so very intimately with the Blessed Mother and wrote,

“O Blessed Virgin, I am close to you, I press up against you in silence, without uttering a word. It

is Advent. Our heart quivers. My Mother, I take refuge with you, this

Advent is also for me a true Advent, you know it. Put your hand on my

heart, o holy Virgin. Do you feel it? Isn’t it so, this poor machine

will not be able to go well much farther, anymore? My holy Mother, I

wait with you. We listen to the palpitations of His Heart. However, O

Holy Virgin, I die of desire to really hold Him in my arms with you. My

Holy Mother, forgive my boldness, I am dust, I know it, but I am driven

irresistibly; I ardently desire His arrival in me. I would hold him

tightly in my arms, to protect him from all offenses, to delight Him

with my love, to avoid the wounds caused by the coldness of hearts. May

he listen to the soft murmur of my lips, the ardent quivering of my

heart! O my little Jesus, I beg you, look at me, plunge your eyes in

mine! I cover them with kisses, in order to hide from them all that

could cause you sorrow. Sleep, Jesus. I, during this time, will beg for

you the love of hearts. I will ask of them that they will let themselves

be filled with your graces, to receive your spirit so that you can come

back to life in them.”(page 77)

“O Blessed Virgin, I am close to you, I press up against you in silence, without uttering a word. It

is Advent. Our heart quivers. My Mother, I take refuge with you, this

Advent is also for me a true Advent, you know it. Put your hand on my

heart, o holy Virgin. Do you feel it? Isn’t it so, this poor machine

will not be able to go well much farther, anymore? My holy Mother, I

wait with you. We listen to the palpitations of His Heart. However, O

Holy Virgin, I die of desire to really hold Him in my arms with you. My

Holy Mother, forgive my boldness, I am dust, I know it, but I am driven

irresistibly; I ardently desire His arrival in me. I would hold him

tightly in my arms, to protect him from all offenses, to delight Him

with my love, to avoid the wounds caused by the coldness of hearts. May

he listen to the soft murmur of my lips, the ardent quivering of my

heart! O my little Jesus, I beg you, look at me, plunge your eyes in

mine! I cover them with kisses, in order to hide from them all that

could cause you sorrow. Sleep, Jesus. I, during this time, will beg for

you the love of hearts. I will ask of them that they will let themselves

be filled with your graces, to receive your spirit so that you can come

back to life in them.”(page 77)

The depth of intimacy in this Advent prayer is incredibly profound, the imagery so tangible, her humanity so prominent.She has the simplicity of a child, as well as a childlike boldness.She states her union with the Blessed Mother; together they await the birth of the infant Jesus, listening.

What Sr. Maria Margit has, she shares and wants to build in others. So the circle of her concern and love widens from the profound intimacy with the Blessed Mother to all.

Suggestion: Pray Venerable Maria Margit’s Advent prayer today!

From http://visitationspirit.org/blog/:

Our Advent series this year will focus on the Advent prayers , reflections and experiences of various Visitation Sisters, both our mystics as well as other members of of the Visitation Order of Holy Mary.

We begin with newly declared Venerable Sister Maria Margit Bogner, VHM of Erd, Hungary (1905-1933) whose Cause for beatification is in process. In

a private audience this past June 2012, with prefect of the

Congregation for the Causes of the Saints, Cardinal Angelo Amato, Pope

Benedict XVI approved the “heroic virtue” of Servant of God Maria

Margit Bogner.

We begin with newly declared Venerable Sister Maria Margit Bogner, VHM of Erd, Hungary (1905-1933) whose Cause for beatification is in process. In

a private audience this past June 2012, with prefect of the

Congregation for the Causes of the Saints, Cardinal Angelo Amato, Pope

Benedict XVI approved the “heroic virtue” of Servant of God Maria

Margit Bogner.Sister Maria Margit lived the liturgical seasons fully, both interiorly and in community. Her interior reflections and prayers were manifested in her diaries and other journal writings. We take these excerpts from the book “Une Tombe Pres du Danube”by Elemer Csavossy SJ, in French, translated by the current blogger.

Sister Maria Margit’s ardor grew throughout Advent. She also prayed in conjunction so very intimately with the Blessed Mother and wrote,

“O Blessed Virgin, I am close to you, I press up against you in silence, without uttering a word. It

is Advent. Our heart quivers. My Mother, I take refuge with you, this

Advent is also for me a true Advent, you know it. Put your hand on my

heart, o holy Virgin. Do you feel it? Isn’t it so, this poor machine

will not be able to go well much farther, anymore? My holy Mother, I

wait with you. We listen to the palpitations of His Heart. However, O

Holy Virgin, I die of desire to really hold Him in my arms with you. My

Holy Mother, forgive my boldness, I am dust, I know it, but I am driven

irresistibly; I ardently desire His arrival in me. I would hold him

tightly in my arms, to protect him from all offenses, to delight Him

with my love, to avoid the wounds caused by the coldness of hearts. May

he listen to the soft murmur of my lips, the ardent quivering of my

heart! O my little Jesus, I beg you, look at me, plunge your eyes in

mine! I cover them with kisses, in order to hide from them all that

could cause you sorrow. Sleep, Jesus. I, during this time, will beg for

you the love of hearts. I will ask of them that they will let themselves

be filled with your graces, to receive your spirit so that you can come

back to life in them.”(page 77)

“O Blessed Virgin, I am close to you, I press up against you in silence, without uttering a word. It

is Advent. Our heart quivers. My Mother, I take refuge with you, this

Advent is also for me a true Advent, you know it. Put your hand on my

heart, o holy Virgin. Do you feel it? Isn’t it so, this poor machine

will not be able to go well much farther, anymore? My holy Mother, I

wait with you. We listen to the palpitations of His Heart. However, O

Holy Virgin, I die of desire to really hold Him in my arms with you. My

Holy Mother, forgive my boldness, I am dust, I know it, but I am driven

irresistibly; I ardently desire His arrival in me. I would hold him

tightly in my arms, to protect him from all offenses, to delight Him

with my love, to avoid the wounds caused by the coldness of hearts. May

he listen to the soft murmur of my lips, the ardent quivering of my

heart! O my little Jesus, I beg you, look at me, plunge your eyes in

mine! I cover them with kisses, in order to hide from them all that

could cause you sorrow. Sleep, Jesus. I, during this time, will beg for

you the love of hearts. I will ask of them that they will let themselves

be filled with your graces, to receive your spirit so that you can come

back to life in them.”(page 77)The depth of intimacy in this Advent prayer is incredibly profound, the imagery so tangible, her humanity so prominent.She has the simplicity of a child, as well as a childlike boldness.She states her union with the Blessed Mother; together they await the birth of the infant Jesus, listening.

What Sr. Maria Margit has, she shares and wants to build in others. So the circle of her concern and love widens from the profound intimacy with the Blessed Mother to all.

Suggestion: Pray Venerable Maria Margit’s Advent prayer today!

Friday, November 30, 2012

St. Andrew's Christmas Novena 11/30 to 12/25

From the Feast of Saint Andrew the Apostle to the Nativity of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ one may begin a special prayer, simply called the "Christmas Prayer" to obtain favors if one's requests are in accordance with God's will.

It is believed that whoever recites the following prayer with a pious heart15 times a day from November 30th (this year December 1) to December 25th, will obtain whatever is asked.

This Christmas prayer carries an Imprimatur from Archbishop Michael Augustine of New York City during the Pontificate of Pope Leo XIII on February 6, 1897. Since one should say this short prayer 15 times a day, it is recommended to memorize it below so you can say it wherever you are or clip the prayer card below and insert in your missal, Divine Office book or put on your bathroom mirror or wherever you would see it the most.

Part 5 LIfe of St. Teresa of Avila by St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross

13. Spread of the Reform

Again, it was the burning

desire for the salvation of souls that led Teresa to new action. One day a

Franciscan from the missions visited her and told her about the sad spiritual

and moral condition of people in heathen lands. Shaken, she withdrew into her

hermitage in the garden. “I cried to the Savior, I pleaded with him for the

means of winning souls for him because the evil enemy robs him of so many. I

asked him to help himself a little by my prayers, because that was all I could

offer him.” After petitioning like this for many days, the Lord appeared to her

and spoke the comforting words, “Wait a little while, my daughter, and you will

see great things.” Six months later came the fulfillment of this promise.

In the spring of the year

1567 she received the news of an upcoming visit to Spain by the Carmelite

General, Giovanni Battista Rossi (Rubeo). “This was something most unusual. The

generals of our order always have been situated in Rome. None had ever come to

Spain before.” The nun who had left her monastery and founded a new one had

reason to be afraid of the arrival of her highest superior. He had the power to

destroy her work. With the consent of the bishop of Avila who had jurisdiction

of her house, Teresa invited the General to visit. He came, and Teresa gave him

a completely candid account of the entire history of the foundation. What he saw

convinced him of the spirit that ruled in this little monastery and he was moved

to tears. It was evident that here was a perfect realization of the goal for

which he had come to Spain. He was considering a reform of the entire Order, a

return to the old traditions, but he had not risked proceeding as radically as

Teresa. King Philip II had called him to Spain to renew discipline in the

monasteries of his land. He had found little friendly reception in other places.

Now he confided his concerns to Teresa. For her part, she responded with love

and with a daughter’s trust. When he departed from Avila, he left Teresa with

permits to found additional women’s monasteries of the reform. All of these

monasteries were to be directly under the general. No provincial was to have the

right to hinder their foundation or to involve himself in their affairs. When he

returned to Madrid, Fr. Rubeo spoke enthusiastically to the king about Teresa

and her work. Philip II asked for her prayers and those of her daughters, and

was from then on the most powerful friend and protector of the reform.

After

returning to Rome, the Father General gave

the saint even more power: to found two monasteries for men according to the

Primitive Rule if she could obtain the permission of the present provincial

and that of his predecessor. This permission was obtained for her by the bishop

of Avila, who himself had been the first to express the wish for monasteries of

friars of the reform. Teresa now found herself in an unusual position. Instead

of a quiet little monastery to which she could retreat with a few selected

souls, she was now to found an entire order for men and women. “And only a poor,

unshod Carmelite was there to accomplish this, even though furnished with

permits and the best wishes, but without any means for initiating the work and

without any other support than that of the Lord....”(46)

But this support sufficed. Before long, what was most important for a monastery

of men appeared: the first friars. While she was making the first foundation for

nuns in Medina del Campo, the prior of the Carmelite monastery of the mitigated

rule there, Fr. Antonio de Heredia, energetically stood by Teresa’s side. When

she told him of her plan, he declared himself ready to be the first male

discalced Carmelite. Teresa was surprised and not absolutely happy, because she

did not fully credit him with having the strength to sustain the Primitive

Rule. However, he stayed firm in his decision. A few days later, a companion

for him appeared who was most satisfactory to the saint: a young Carmelite at

that time called John of St. Matthias, who from his early youth had lived a life

of prayer and the strictest self-denial. He had gained the permission of his

superior to follow the Primitive Rule personally. Not satisfied with

this, he was thinking of becoming a Carthusian. Teresa persuaded him, instead,

to become the living cornerstone of the Carmelite Order of the Primitive

Rule.

Some time later a little

house in Duruelo, a hamlet between Avila and Medina del Campo, was offered to

her for the planned foundation. It was in miserable condition, but neither

Teresa nor the two fathers were taken aback by it. Fr. Antonio still needed some

time to end his priorship and put all his affairs in order. In the meantime, Fr.

John joined Holy Mother to acquaint himself with the spirit and rule of life of

the reform under her personal direction. On September 20, 1568 he went to

Duruelo, having been clothed by Teresa in the habit of the reform, which she

herself had made for him. As the Holy Mother had anticipated, he divided the

single room of the pitiful little hut into two cells, an attic room into the

choir, a vestibule into a chapel where he celebrated the first Mass the next

morning. Soon he was considered a saint by the peasants in the neighborhood. On

November 27, Fr. Antonio joined him. Together they now committed themselves to

the Primitive Rule and changed their names. From then on they were called

Anthony of Jesus and John of the Cross.

A few months later the Holy

Mother could visit them and get to know their way of life. She says about this: "I came there during Lent in

the year 1569. It was morning. Father Antonio in his always cheerful mood was

sweeping the doorway to the church. “What does this mean, my father,” I said,

“and where is your self-respect?” ...”Oh, cursed be the time when I paid

attention to that,” he answered chuckling. I went into the chapel and was seized

by the spirit of fervor and poverty with which God had filled it. I was not the

only one so moved. Two merchants with whom I was friendly and who had

accompanied me from Medina del Campo looked at the house with me. They could

only weep. There were crosses and skulls everywhere. I will never forget a

little wooden cross over a holy water font to which an image of the Savior had

been glued. This image was made of simple paper; however, it flooded me with

more devotion than if it had been very valuable and beautifully made. The choir,

once an attic room, was raised in the middle so that the fathers could

comfortably pray the Office. But one still had to bow deeply when entering. At

both sides of the church, there were two little hermitages where they could only

sit or lie down and even so their heads would touch the roof. The floor was so

damp that they had to put straw on it. I learned that the fathers, instead of

going to sleep after matins, retreated to these little hermitages and meditated

there until prime. In fact, they once were praying in such recollection that

when snow fell on them through the slats in the roof, they did not notice it at

all, and returned to the choir without it occurring to them even to shake their

robes.

Duruelo was the cradle of

the male branch of the reformed Carmel. It spread vigorously

from there, always directed by the Holy Mother’s prayer and illuminating

suggestions, but nevertheless relatively independent. The humble little John of

the Cross, the great saint of the church, inspired it with the spirit. But he

was entirely a person of prayer, of penance. Others took on the external

direction. Besides Fr. Antonio, there were the enthusiastic Italians, Fr.

Mariano and Fr. Nicolás Doria. But, above all, the most faithful support for the

Holy Mother during her last years was, as she was convinced, the choice

instrument of the reform, the youthful, brilliantly gifted Fr. Jerónimo Gracián

of the Mother of God.

Teresa herself had hardly

any time for quiet monastic life after she left the peace of St. Joseph’s upon

founding the first daughter house in Medina del Campo. She was called now here,

now there, to establish new houses of the reform. Despite her always fragile

health and increasing age, she indefatigably undertook the most difficult

journeys as often as the Lord’s service required. Everywhere there were hard

battles to endure: Sometimes there were difficulties with the spiritual and

civil authorities; sometimes, the lack of a suitable house and the basic

necessities of life; sometimes, disagreements with upper class founders who made

impossible demands of the monasteries. When finally all obstacles had been

overcome and everything organized so that the true life of Carmel could begin,

she who had done it all had, without pause, to move on to new tasks. The only

consolation she had was that a new garden was blooming for the Lord to enjoy.

14. Prioress at the

Monastery of the Incarnation

While the spiritual gardens

of Mother Teresa were spreading their lovely fragrance over all of Spain, the

Monastery of the Incarnation, her former home, was in a sad state. Income had

not increased in proportion to the number of nuns, and since they were used to

living comfortably and not (as in the reformed Carmel) to finding their greatest

joy in holy poverty, discontent and slackening of spirit spread. In the year

1570, Fr. Fernández of the Order of St. Dominic came to this house. He was the

apostolic visitator entrusted by Pope Pius V with examining the disciplinary

state of monasteries in Castile. Since he had already

become thoroughly acquainted with some monasteries of the reform, the contrast

must have shocked him. He thought of a radical remedy. By the authority of his

position, he named Mother Teresa as prioress of the Monastery of the Incarnation

and ordered her to return to Avila at once to assume her position. In the midst

of her work for the reform, she now had to undertake the task that for all

intents and purposes appeared impossible. Exhorted by the Lord himself, she

declared her readiness. However, with the agreement of Fr. Fernández, she gave a

written statement that she personally would continue to follow the Primitive

Rule. One can imagine the vehement indignation of the nuns who were to have

a prioress sent to them one not elected by them a sister of theirs who had left

them eight years earlier and whom they considered as an adventuress, a

mischief-maker. The storm broke as the provincial led her into the house. Fr.

Angel de Salazar could not make himself heard in the noisy gathering. The “Te

Deum” that he intoned was drowned out by the sounds of indignation. Teresa’s

goodness and humility finally brought about enough quiet for the sisters to go

to their cells and to tolerate her presence in the house.

They were saving the

decisive declarations for the first chapter meeting. But how amazed they were

when they entered the chapter room at the sound of the bell to see in the

prioress’ seat the statue of our dear Lady, the Queen of Carmel, with the keys

to the monastery in her hands and the new prioress at her feet. Their hearts

were conquered even before Teresa began to speak and in her indisputably loving

manner presented to them how she conceived of and intended to conduct her

office. In a short time, under her wise and temperate direction, above all by

the influence of her character and conduct, the spirit of the house was renewed.

Her greatest support in this was Fr. John of the Cross, whom she called to Avila

as confessor for the monastery.

This time of greatest

expenditure of energy when Teresa, along with being prioress of the Monastery of

the Incarnation, retained the spiritual direction of her eight reformed

monasteries, was also a time of the greatest attestation of grace. At that time

she had a vision which she herself described as a “spiritual marriage.” On

November 18, 1572, the Lord appeared to her during Holy Communion. “He offered

me his right hand and spoke, ‘See this nail. It is the sign of our union. From

this day on you are my bride. Up to now you had not earned it. But now you will

not only see me as your Creator, your King, your God, but from now on you will

care for my honor as my true bride. My honor is yours; your glory is mine.’”

From that moment on, she found herself united blissfully with the Lord, a union

which remained with her for the entire last decade of her life, her own life

mortified, “full of the inexpressible joy of having found her true rest, and of

the sense that Jesus Christ was living in her.”(47)

She characterized as the first result of this union “such a complete

forgetfulness of self that it truly seems as if this soul had lost its own

being. It no longer recognizes itself. It no longer thinks about heaven for

itself, about life, about honor. The only thing she cares about any longer is

the honor of God.” The second result is an inner desire for suffering, a desire,

however, that no longer disturbs her soul as earlier. She desires with such

fervor that God’s will be fulfilled in her that everything which pleases the

divine Master seems good to her. If he wants her to suffer, she is happy; if he

does not, his will be done.

But the following surprised

me the most. This soul whose life has been martyrdom, because of her strong

desire to enjoy the vision of God, has now become so consumed by the wish to

serve him, to glorify his name, and to be useful to other souls that, far from

wishing to die, she would like to live for many years in the greatest

suffering....

In this soul there is no

more interior pain and no more dryness, but only a sweet and constant joy.

Should she for a short time be less attentive to the presence of God, he himself

immediately awakens her. He works to bring her to complete perfection and

imparts his doctrines in a completely hidden way in the midst of such a deep

peace that it reminds me of the building of Solomon’s temple. Actually, the soul

becomes the temple of God where only God alone and the

soul mutually delight in each other in greatest quiet.

15. Doing Battle for Her

Life’s Work

The greatest grace that can

befall a soul was probably necessary to strengthen the saint for the storm that

was soon to break over the reform. Even during her term as prioress, she had to

resume her journeys of foundation and leave a vicaress in charge in Avila. At

the end of her years as prioress it was only with some effort that she stopped

the nuns from re-electing her. Those who had so struggled against her assuming

the position clung to her with such great love. Her humility and goodness, her

superior intelligence and wise moderation in this case had been able to bridge

the rift between the “calced” and the “discalced.” Her spiritual sons were not

so lucky. They had founded new monasteries in addition to the two for which the

general of the Order, Fr. Rubeo, had previously given Teresa authorization. They

had the permission of the apostolic visitator from Andalusia, Fr. Vargas, but no

arrangement with the Order’s superiors. Their extraordinary penances (which

often caused the saint herself concern) and their zeal soon aroused the

admiration of the people. This, along with the evident preference for the

monasteries of the reform on the part of the apostolic visitator, made those not

of the reform fear they themselves would soon be pushed entirely into the

background, even that the reform might be imposed on the entire Order. Their

envoys turned the general in Rome completely against the discalced as

disobedient and as agitators. To suppress their “revolt,” Fr. Tostado, a

Portuguese Carmelite with special authority, was sent to Spain. A clash between

the two branches of the Order ensued, which must have filled the heart of the

humble and peace-loving Holy Mother with the greatest pain. In addition, it

appeared that her entire work was threatened. She herself was called “a

gadabout” by the new papal nuncio in Spain, “disobedient, ambitious, who

presumes to teach others like a doctor of the church despite the prohibition of

Saint Paul.” She was ordered to choose one of the reformed monasteries as her

permanent residence and to make no further trips. How grateful she would have

been for the quiet in the monastery of Toledo which Fr. Gracián suggested to

her, had there not been such a hostile design behind the command! All the

monasteries of the reform were prohibited from taking in novices, condemning

them to extinction. Her beloved sons were reviled and persecuted. Fr. John of

the Cross, who had always kept himself far from all conflict, was even secretly

abducted and kept in humiliating confinement in the monastery of the “calced” in

Toledo. He was cruelly abused until the Blessed Virgin, his protectress since

childhood, miraculously freed him. In this storm that finally made everyone lose

courage, the Holy Mother alone stood erect. Together with her daughters, she

stormed heaven. She was indefatigable in encouraging her sons with letters and

advice, in calling her friends for help, in presenting the true circumstances to

the Father. General who had once been so good to her, in appealing for

protection from her most powerful patron, the king. And finally she arrived at

the solution that she recommended as the only possible one: the complete

separation of the calced from the discalced Carmelites into two provinces. The

Congregation of Religious in Rome had been occupied with the unfortunate

conflict for a long time. A well- informed cardinal, whom Pope Gregory XIII

questioned concerning the state of affairs, responded, “The Congregation has

thoroughly investigated all the complaints of the Carmelites of the Mitigated

Rule. It comes down to the following: Those with the Mitigated Rule

fear that the reform will finally reform them also.” The pope then decided that

the monasteries of Carmelite friars and nuns of the reform were to constitute a

province of their own under a provincial chosen by them. A brief dated June 27,

1580 announced this decision. In March of 1581, the chapter of Alcalá elected

Fr. Jerónimo Gracián as its first provincial in accordance with the wishes of

the Holy Mother.

16. The End

Teresa greeted the end of

the years of suffering with overflowing thanks. “God alone knew in full about

the bitterness, and now only he alone knows of the boundless joy that fills my

soul, as I see the end of these many torments. I wish the whole world would

thank God with me! Now we are all at peace, calced and discalced Carmelites, and

nothing is to stop us from serving God. Now then, my brothers and sisters, let

us hurry to offer ourselves up for the honor of the divine Master who has heard

our prayers so well.” During the short span of time still given to her, she

herself sacrificed her final strength for new journeys to make foundations. The

erection of the monastery in Burgos, the last one that she brought to life, cost

her much effort and time. She had left Avila on January 2, 1582 to go there. It

was July before she could begin the trip home, but she was not to reach the

desired goal any more. After she had visited a number of other monasteries of

the nuns, Fr. Antonio of Jesus brought her to Alba to comply with a wish of the

Duchess María Henríquez, the great patroness of that monastery. Completely

exhausted, Teresa arrived on September 20. According to a number of witnesses,

she had predicted some years earlier that she would die at this place and at

this time. Even though the attending physician saw her condition as hopeless,

she continued to take part in all the monastic exercises until September 29.

Then she had to lie down. On October 2, in accordance with her wish, Fr. Antonio

heard her last confession. On the third she requested Viaticum. An eyewitness

gave this report: “At the moment when the Blessed Sacrament was brought into her

cell, the Holy Mother raised herself without anyone’s help and got on her knees.

She would even have gotten out of her bed if she had not been prevented. Her

expression was very beautiful and radiated divine love. With a lively expression

of joy and piety, she spoke such exalted divine words to the Lord that we were

all filled with great devotion.” During the day she repeated again and again the

words from the “Miserere” (Psalm 51): “Cor contritum et humiliatum, Deus, no

despicies” (a broken and contrite heart, God, you will not despise). In the

evening she requested to be anointed. Concerning her last day, October 4, we

again have an eyewitness account by Sr. María of St. Francis:

"On the morning of the feast

of St. Francis, at about 7 o’clock, our Holy Mother turned on her side toward the nuns, a crucifix in her

hand, her expression more beautiful, more glowing, than I had ever seen it

during her life. I do not know how her wrinkles disappeared, since the Holy

Mother, in view of her great age and her continual suffering, had very deep

ones. She remained in this position in prayer full of deep peace and great

repose. Occasionally she gave some outward sign of surprise or amazement. But

everything proceeded in great repose. It seemed as if she were hearing a voice

which she answered. Her facial expression was so wondrously changed that it

looked like a celestial body to us. Thus immersed in prayer, happy and smiling,

she went out of this world into eternal life."

The wondrous events that

occurred at the Saint’s burial, the incorrupt state of her body that was

determined by repeated disinterments, the numerous miracles that she worked

during her life and then really in earnest after her death, the enthusiastic

devotion of the entire Spanish people for their saint all of this led to the

initiation of the investigations preparatory to her canonization, already in the

year 1595. Paul V declared her blessed in a brief on April 24, 1614. Her

canonization by Gregory XV followed on March 22, 1622. Her feast day was

designated as October 15, because the ten days after her death were dropped

(October 5-14, 1582) due to the Gregorian calendar reform.

Luis de León(48)

said of Teresa: “I neither saw nor knew the saint during her lifetime. But

today, albeit she is in heaven, I know her and see her in her two living

reflections, that is, in her daughters and in her writings....” Actually, there

are few saints as humanly near to us as our Holy Mother. Her writings, which she

penned as they came to her, in obedience to the order of her confessor, wedged

between all of her burdens and work, serve as classical masterpieces of Spanish

literature. In incomparably clear, simple and sincere language they tell of the

wonders of grace that God worked in a chosen soul. They tell of the

indefatigable efforts of a woman with the daring and strength of a man,

revealing natural intelligence and heavenly wisdom, a deep knowledge of human

nature and a rich spirit’s innate sense of humor, the infinite love of a heart

tender as a bride’s and kind as a mother’s. The great family of religious(49)

that she founded, all who have been given the enormous grace of being called her

sons and daughters, look up with thankful love to their Holy Mother and have no

other desire than to be filled by her spirit, to walk hand in hand with her the

way of perfection to its goal.

++++++++++++++++++

Life and Work of St. Teresa of Jesus

1. [In fact, recent studies have shown that Teresa was of

Jewish ancestry; see Teofanes Egido, “The Historical Setting of St. Teresa’s

Life,” Carmelite Studies 1 (1980): 122-182. Throughout this essay, Edith

Stein writes in light of the historical data available to her at the time. Some

minor corrections (of dates, etc.) have been inserted into the text of this

translation, but the basic presentation remains as she wrote it. Tr.]

2. [According to recent research, the dedication of the chapel

of the Monastery of the Incarnation took place in the same year (1515) as

Teresa’s birth, but not on the same day; see Efrén de la Madre de Dios and Otger

Steggink, Tiempo y Vida de Santa Teresa, 2d ed. (Madrid: Biblioteca de

Autores Cristianos, 1977), pp. 22-25, 90. Tr.]

3. Throughout this essay, Edith Stein quotes from a

comparatively free German translation of Teresa’s works available to her, and

ordinarily without references. Here, for the convenience of the reader, we have

used the ICS translations of the corresponding passages, with appropriate

references, whenever these could be located and did not substantially

alter Edith Stein’s line of thought or the meaning of the quotation in German.

These texts may be found in The Collected Works of St. Teresa of Avila,

trans. Kieran Kavanaugh and Otilio Rodriguez, vols. 1-3 (Washington, DC: ICS

Publications, 1976- 1985). The following system of abbreviations is used:

Foundations = Book of Foundations; Life = Book of Her Life; IC = Interior

Castle; Way = Way of Perfection; Testimonies = Spiritual Testimonies. For

the first four works, the Arabic numerals indicate the chapter and section

number from which the quotation was taken. The Interior Castle is also

divided into seven “dwelling places,” indicated by a Roman numeral. Thus a

passage marked “IC, 3, 2, 1” would be taken from the first section of the

second chapter in the third “dwelling place” of the Interior Castle. Tr.]

4. According to the saint. Fourteen in the latest research.

[Ed.]

5. In particular in her Life, Way of Perfection, and

Interior Castle. The references cited so far are from her Life.

However, it is recommended that the reader who has not yet dealt with spiritual

writings begin with the Way of Perfection. The presentation of the Our

Father contained in it is a model example of contemplative prayer.

6. Oettingen-Spieberg, Geschichte der hl. Teresia

[Biography of St Teresa], Regensberg: Habbel, vol. I, p. 313f.

7. Probably an error by Edith Stein. The provincial at that

time was Fr. Gregorio Fernández (1559-1561). Fr. Angel de Salazar was prior in

Avila in 1541. He was provincial from 1551-1553. [Ed.]

8. It is said that our Holy Mother at first wore sandals that

left the feet uncovered, as our friars still do today. It was only when her

dainty foot was admired once during a trip that she introduced hempen sandals

called “alpargatas.” [Ed.]

9. See note 8. [Ed.]

10. After she had discovered and tested the most appropriate

regimen in living with her daughters, she wrote her “constitutions,” which

except for a few minor changes today continue to contain the valid rules of her

order. They are contained in her writings. [See Collected Works of St.

Teresa, vol. 3, pp. 319-333. Tr.]

11. See note 8. [Ed.]

12. Interior Castle, seventh dwelling places, chap. 3.

[The text does not appear in precisely this form in the ICS translation. Tr.]

13. A learned Augustinian who published the first printed

edition of Teresa’s writings (1588).

14. At her death Teresa left behind fourteen male and sixteen

female monasteries of the reform. Soon thereafter the Order spread to France.

Today it is established all over the world. A great number of lay people are

united with it by the Secular Order and the Scapular Fraternity. The Teresian

Prayer Organization (at the Carmelite Monastery in Würzburg) assembles everyone

who wants to intercede for the needs of the Holy Church and the Holy Father into

a great prayer army, and lets them participate in all the good works of the

Carmelite order.

Part 4 LIfe of St. Teresa of Avila by St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross

10. New Tests

The first difficulty arose

from her own ignorance of mystical theology. In her deep humility, she could not

imagine how an unworthy person (as in her opinion she was) could be so richly

laden with such extraordinary favors. Of course, as long as the favors during

prayer lasted she could not doubt their authenticity. But in between she was

plagued by fears that these mystical states were deceptions of the devil. On the

basis of her experience, Teresa later said again and again how necessary it is

for a soul that is going the way of the interior life to have the guidance of a

learned and enlightened spiritual director. Fr. Vicente Barrón, who had so

charitably stood by her after the death of her father, had been called away from

Avila some time earlier. In her need, upon the advice and through the mediation

of a dear friend, the pious nobleman Francisco de Salcedo, she turned to Gaspar

Daza, a priest who was considered throughout the city to be as holy as he was

learned. His evaluation was devastating. He interpreted all of her favors during

prayer as deceptions of the devil and advised her to cease entirely what she had

been doing up to now. The saint fell into the uttermost distress showered by

favors from heaven while at the same time, according to the theological expert,

in the gravest danger, and directed to pull back from the supernatural

influences! There appeared one more way out of her distress. A short time

earlier a college of the Society of Jesus had been started in Avila. Teresa, who

had the greatest admiration for the new order, heard this with joy, but up to

now had not dared to speak with one of the greatly renowned fathers. Now she

took refuge in them, and this was her deliverance. Fr. Juan de Prádanos

completely reassured her about the origin of her mystical states and advised her

to continue on this path. He only found it necessary that she make herself

worthy of the favors by strict mortifications. As she said, “mortification” was

at that time a word virtually unknown to her. But with her characteristic

decisiveness, she took up the suggestion and began to accustom herself to severe

penances. Recognizing that her weak health would not be able to stand such a

severe life, P. Prádanos easily helped her with this. “Without doubt, my

daughter,” he said, “God sends you so many illnesses in order to make up for

those mortifications that you do not practice. So do not be afraid. Your

mortifications cannot hurt you.” And in fact Teresa’s health improved because of

this new lifestyle.

Even though her new

spiritual director had no doubt about the heavenly origin of her favors during

prayer, he still thought it a good idea to impose on her some constraint in her

manner of meditating and to instruct her in resisting the stream of favors. But

even this restriction was soon to be lifted again. St. Francis Borgia visited

the Jesuit college and to get his evaluation, Fr. Prádanos asked him to speak

with Teresa. She herself writes about this:

I let him...know the state

of my soul. After listening to me, he told me that everything happening in me

came from the spirit of God. He called my behavior good so far. But he said that

in the future I should offer no more resistance. He advised me always to begin

my prayers by meditating on one of the mysteries of the passion. If then without

my assistance the Lord transported my spirit into a supernatural state, I should

surrender to his guidance.... He left me completely consoled.

If the saint herself was

calmed by such weighty testimony, it was not so in her surroundings. In spite of

the testimony of St. Francis Borgia, despite the sympathetic guidance she found,

soon after the recall of Fr. Prádanos, in his very young but saintly confrere,

Fr. Baltasar Alvarez, her devoted friends did not stop worrying about her. They

asked others in for advice, and soon everyone in the city was talking about the

unusual phenomena at the Monastery of the Incarnation and warning the young

Jesuit not to let himself be deceived by his penitent. Even though he placed no

credence in these voices, he did think it advisable to pose Teresa some

difficult tests. He denied her solitude, and once withheld Holy Communion from

her for twenty days. She submitted to all orders. But it was no wonder that

unrest once more arose in her heart also, since everyone else doubted her or

appeared to doubt her. Her deliverance was the goodness of the Lord who calmed

her again and again, who enraptured her right in the middle of the mandatory

conversations, since solitary prayer was taken from her. Above all, he

strengthened her to persist faithfully in the way of obedience no matter how

hard it was. Her reward was new, continually greater favors. She felt the

presence of the Savior by her side often for entire days. At first he came to

her invisibly, but later also in a visible form.

The Savior almost always

appeared to me visibly in risen form. When I saw him in the holy Host, he was in

this transfigured form. Sometimes when I was tired or sad, he showed me his

wounds to encourage me. He also appeared to me hanging on the cross. I saw him

in the garden; finally, I saw him carrying the cross. When he appeared to me in

such a form, it was, I repeat, because of a need in my soul or for the

consolation of various other persons; still his body was always glorified.

These appearances increased

Teresa’s love and strengthened her in the certainty that it was none other than

the Lord who was visiting her with his favors. So it must have been all the more

painful to her when, in the absence of Fr. Alvarez, another confessor ordered

her to send the “evil spirit” away each time it appeared by making the sign of

the cross and a gesture of contempt. She also obeyed this command. But at the

same time she fell at the feet of the Lord and pleaded with him for forgiveness:

“Oh Savior, you know when I act like this toward you that I do it only out of

love for you because I want to submit obediently to him whom you have appointed

in your Church to take your place for me.” And Jesus calmed her. “Be comforted,

my daughter, you do well to obey. I will reveal the truth.”

In this obedience toward the

church, the saint herself had always seen the surest criterion that a soul was

on the right way.

I know for certain that God

would never allow the devil to delude a soul that mistrusts itself and whose

faith is so strong that it was prepared to endure a thousand deaths for the sake

of one single article of faith. God blesses this noble disposition of the soul

by strengthening its faith and making it ever more fiery. This soul carefully

tries to transform itself so that it is completely in line with the teachings of

the church and for this purpose asks questions of anyone who could elucidate

them. It hangs on so tightly to the church’s creeds that all conceivable

revelations even if it saw heaven opened could never make it vacillate in its

faith even in the minutest article taught by the church....

Should a soul not find in

itself this powerful faith or its delight in devotion not contribute to

increasing its dependence on the holy church, then I say that the soul is on a

path filled with danger. The spirit of God only flows into things that are in

agreement with the holy Scriptures. If there had been the slightest deviation, I

would have been convinced that these things came from the author of lies.

That after each new favor

she grew in humility and love must have pacified the saint herself, and must

also have been an unmistakable sign to the enlightened men of the spirit of the

disposition of her soul.

During that time of unusual

demonstrations of grace and of the severest tests, Teresa also received a

visible sensory image of the glowing love which pierced her heart. “I saw beside

me at my left side an angel in a physical form.... Because of his flaming face,

he seemed to belong to that lofty choir made up only of fire and love.... I saw

a long, golden dart in his hands the end of which glowed like fire. From time to

time the angel pierced my heart with it. When he pulled it out again, I was

entirely inflamed with love for God.” The heart of the saint, which has been

preserved in the monastery of Alba and remains intact to this day, bears a long,

deep wound.

11. Works for the Lord

One who loves feels

compelled to do something for the beloved. Teresa, who even as a child showed

herself to be boldly decisive and ready to act, burned with the desire to show

the Lord her love and thankfulness by action. As a nun in a contemplative

monastery, she seemed to be cut off from all outer activity. So she at least

wanted to do as much as possible to make herself holy. With the permission of

her confessor (Fr. Alvarez) and her highest superior in the Order, she took a

vow always to do what would be the most pleasing to God. To protect her from

uncertainty and from qualms of conscience, the text was later changed to read

that her confessor was to decide what would be perfect at any given time.

But a soul so full of love

could not be satisfied with caring for its own salvation and making the Lord

happy by its own perfection. One day she was transported into hell by a horrible

vision. “I immediately understood that God wanted to show me the place that the

devil had reserved for me and that I deserved for my sins. It lasted hardly a

moment. But even if I live for many more years, I will never be able to forget

it.” She recognizes that from which God’s goodness has preserved her. “The